As a high-intensity, intermittent sport, field hockey demands optimal muscular power, speed, agility, and hormonal readiness to sustain competitive performance.

ObjectiveThis randomized controlled trial compared the effects of Complex-Contrast Training (CCT) and French Contrast Training (FCT) on steroid hormone responses and selected physical performance parameters in tier 3 male field hockey players.

Materials & methodsForty-five players (age: 19.56 ± 1.34 years) were randomly assigned to either a CCT group (n = 15), an FCT group (n = 15), or a regular training group (RTG) (n = 15). Training interventions were conducted thrice weekly for 12 weeks (36 sessions total), each lasting 60 min, following a 2-week familiarization period. Baseline assessment (A1) and 12-week assessment (A2) included serum testosterone (TST) and cortisol (CRSL) concentrations, 50 m sprint time, change of direction speed (CoDs), and countermovement jump (CMJ).

ResultsBoth CCT and FCT groups demonstrated significant improvements in sprint performance (p < 0.001, ⴄ2=0.066), and CoDs (p < 0.001, ⴄ2=0.117), and CMJ (p < 0.001, ⴄ2=0.133), compared to the RTG. TST levels increased significantly in both CCT and FCT (p < 0.001, ⴄ2=0.094), with a greater effect observed in the FCT group. CRSL responses indicated a favorable anabolic-catabolic balance post-training (p < 0.001, ⴄ2=0.056), particularly in the FCT group. Between-group comparisons revealed that FCT produced superior gains in explosive power and hormonal adaptation, while CCT yielded slightly better improvements in sprint performance.

ConclusionsThese findings suggest that both training methods are effective for enhancing steroid hormone profiles and performance variables in competitive field hockey players, with FCT offering a marginal advantage for power-oriented adaptations. Coaches and practitioners may consider incorporating either approach during pre-competition phases to optimize physiological and performance outcomes.

Field hockey is an intense, high-speed team sport that demands a unique combination of physical and physiological adaptations to achieve peak performance, including optimal endocrine responses to training.1,2 The dynamic nature of the game, characterized by rapid accelerations, decelerations, repeated sprints, sudden changes in direction, and explosive actions such as tackles, passes, and shots, places substantial physical and physiological stress on athletes.3,4 To cope with these demands, players must develop advanced levels of muscular power, speed, strength, change of direction speed (CoDs), and endurance.5,6 Moreover, optimal hormonal functioning, particularly involving anabolic and catabolic steroid hormones like testosterone (TST) and cortisol (CRSL), is essential in regulating recovery, muscle adaptation, and overall athletic readiness.1,7

Recent advancements in training science have emphasized the importance of contrast-based methods such as complex training, including complex-contrast (CCT) and French contrast training (FCT), to enhance physical performance, especially in sports like field hockey, where speed and power are critical.2,8,9 Among the numerous physical qualities necessary for successful performance in field hockey, lower-body power, reactive strength, sprint speed, and agility are particularly influential.5,6,10 These qualities are not only decisive during match-play but also serve as key indicators of an athlete's preparedness.11 Consequently, sports scientists and coaches continually seek innovative training protocols that simultaneously improve multiple performance-related variables while considering physiological responses such as hormonal fluctuations.12–14

Complex training is one among them, which utilizes the principle of post-activation potentiation (PAP),15,16 and post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) to augment subsequent explosive output. Specific methods like CCT and FCT have gained growing interest in recent years.17–19 Both methods aim to exploit neuromuscular priming to achieve superior improvements in strength and speed qualities.9 CCT, a subtype of complex training,9 involves the pairing of a high-load strength exercise with a biomechanically similar plyometric movement performed in close succession.20 This technique utilizes the PAP effect, where a heavy resistance movement (e.g., back squat) primes the neuromuscular system for improved performance in an explosive movement (e.g., countermovement jump).15,16 This efficient method promotes both neural and muscular activation and is commonly used for power and strength development.8,19

FCT, another advanced method within the complex training framework, expands upon the basic complex-contrast structure by integrating four sequential exercises: a heavy compound lift, a plyometric movement, a speed-strength movement (such as loaded jump squats), and a reactive or assisted plyometric movement.21 This broader approach targets the entire strength-speed continuum and is considered a more comprehensive, albeit more demanding, contrast training strategy.9 Complex, resistance training modalities not only enhance physical performance but also influence the endocrine system, particularly hormones like TST and CRSL.13,14,22,23 TST plays a vital anabolic role in muscle repair, strength gain, and recovery, while CRSL, a catabolic hormone, is often linked to physical and psychological stress.1 An imbalance between these hormones can signal either effective adaptation or the onset of overtraining.24 Monitoring hormonal responses to different training strategies offers valuable insight into internal load, recovery status, and overall training efficacy, which is particularly important when designing conditioning programs for competitive athletes.25

Although both CCT and FCT have shown promising results in improving explosive performance attributes across various sports, including track and field, basketball, and soccer,15–17,26,27 their application in field hockey remains limited.28–30 This gap is particularly evident among Tier 3 male field hockey players, who represent a developmental stage between amateur and elite performance levels. Effective training interventions at this stage are critical for maximizing performance potential and reducing injury risk.31 Additionally, limited research has examined how these specific training strategies affect hormonal responses in this population, thereby restricting evidence-based recommendations for holistic training approaches in field hockey.3,32 Furthermore, while prior research has often emphasized external performance outcomes, relatively few studies have concurrently examined the underlying physiological mechanisms, such as steroid hormone responses, that drive or limit these improvements.23 Most resistance training and plyometric studies in field hockey rely on traditional or isolated modalities, with insufficient integration of advanced methods like FCT.9 Moreover, the lack of studies evaluating hormonal markers as dependent variables within contrast-based training models limits the applicability of current findings for practitioners who must manage both performance outcomes and athlete well-being.23

Given these gaps, there is a strong need for experimental studies that not only compare the efficacy of CCT and FCT on key physical performance metrics but also consider their impact on steroid hormone markers. This randomized controlled trial (RCT) aims to address this gap by investigating the effects of both training modalities within the broader complex training paradigm on physical performance (including countermovement jump (CMJ) height, linear sprint speed, and CoDs) and steroid hormone responses (TST and CRSL) among Tier 3 male field hockey players. The ultimate goal is to determine the comparative effectiveness and physiological suitability of these two complex training variants in optimizing performance and endocrine balance in this emerging athletic population.

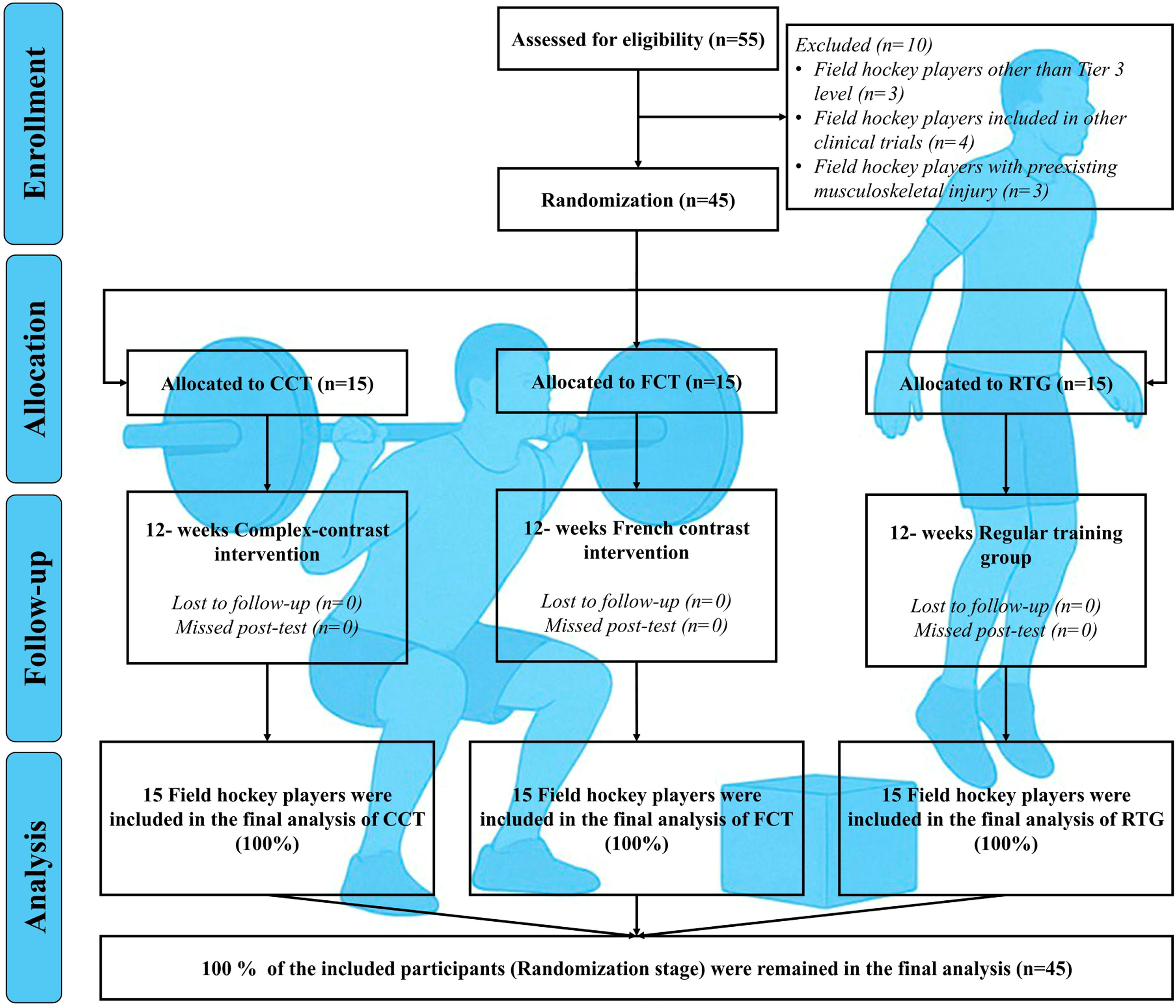

Methods and materialsParticipants and eligibility (Inclusion/Exclusion) criteriaA total of 55 male field hockey players from Kerala, India, were initially approached for the study. Inclusion criteria required participants to be Tier 3 field hockey players aged 18–25 years, with a minimum of six years of continuous competitive experience, and willing to provide informed consent and comply with all study procedures. All eligible players were National/University-level athletes (Tier 3),33 and received both verbal and written explanations of the study before providing written consent. Exclusion criteria led to the removal of three players classified as Tier 2, followed by the exclusion of three athletes with 6 months of pre-existing musculoskeletal injuries and four who were already participating in another experimental program. Additionally, players were excluded if they belonged to Tier 1 or Tier 4 classifications or had any medical condition contraindicating high-intensity physical training, resulting in a final eligible sample of 45 participants (Fig. 1).

Study designThis study employed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Group × Time design), incorporating purposive sampling to apply the initial inclusion criteria for participant selection. Following the baseline assessment (A1), a total of 45 tier 3 players from field hockey were randomly assigned into three groups: two experimental groups, such as CCT (n = 15) and FCT (n = 15) and one control group, termed Regular Training Group (RTG, n = 15). Prior to the 12-week intervention, players in the experimental groups underwent a 2-week familiarization period to ensure proper technique and adaptation to training protocols. Meanwhile, the control group continued with their regular field hockey training. The training programs for the CCT and FCT groups followed a structured progressive overload model, individualized based on each player's one-repetition maximum (1-RM). Outcome measures included steroid hormone levels and physical fitness variables, assessed at two time points: A1 and 12-week assessment (A2). All 45 players completed the full intervention and were included in the A2 assessment. The overall sampling flow and participant distribution across different stages are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Randomization and blindingPlayers were randomly assigned to one of three groups: CCT, FCT, or RTG, using computer-generated random numbers via https://www.randomizer.org/. To ensure allocation concealment, sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes were prepared by an independent researcher and delivered to the principal investigator immediately before the familiarization phase. Due to the nature of the training interventions, blinding of players and the primary researcher was not feasible; however, outcome assessors, laboratory personnel analyzing biomarkers, and data analysts were blinded to group assignments throughout the study to minimize potential bias.

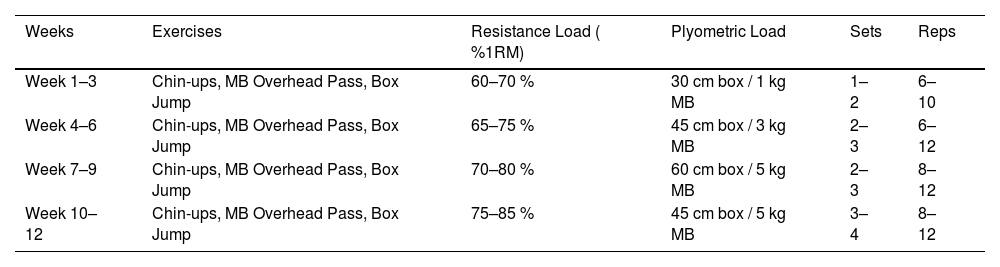

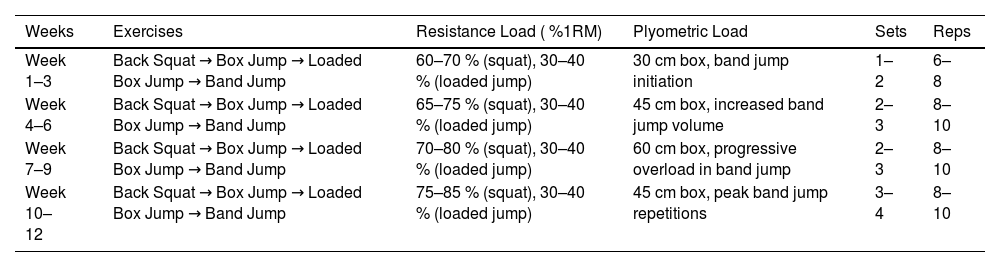

Intervention protocolThe study incorporated two structured training interventions, CCT and FCT, delivered over sessions lasting approximately 60 min each. Both training protocols were preceded by a standardized warm-up and followed by a cooling-down routine. Table 1 presents the weekly structure of the CCT program, which combines heavy resistance exercises with plyometric components to enhance neuromuscular efficiency. Table 2 details the FCT protocol, integrating four exercise modalities: slow-force, plyometric, ballistic, and accelerated movements in a specific sequence to optimize post-activation performance potentiation.

12 weeks of complex-contrast training procedures.

MB: Medicine ball; RM: Repetition maximum; Training Flow: Each set included a high-load resistance movement (e.g., Chin-up) immediately followed by a biomechanically similar low-load plyometric (e.g., Box Jump);9 Recovery: Adequate rest (1–2 min) was provided between pairs.

12 weeks of French contrast training procedures.

RM: Repletion maximum; Training Flow: Each set included a sequence of: Heavy compound lift (Back Squat), Plyometric movement (Box Jump), Weighted Plyometric (Loaded Box Jump at 30–40 % 1RM), Assisted Plyometric (Band-assisted Jump;9 Recovery: Short rest between exercises (15–30 s), longer between sets (2–3 mins).

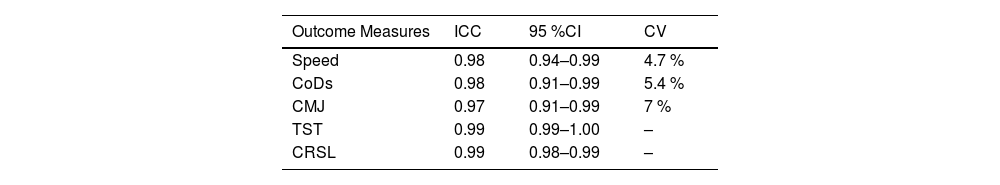

The characteristics of the players were assessed during the A1 assessment and included stature (height), chronological age, weight, and body mass index (BMI). Stature was measured using a standard stadiometer (MCP 2 m/200 cm Roll Ruler Wall Mounted Growth Stature Meter), and weight was measured using a digital weighing machine (HD-93 Digital Weighing Machine). BMI was calculated using the formula weight/height² (m²). Physical outcome measures included speed, change of direction (CoDs), and countermovement jump (CMJ), while total serum testosterone (TST) and cortisol (CRSL) levels were classified as steroid hormones, which were evaluated through blood sample analysis. All outcome measures were collected during both the A1 and A2 assessments, which were conducted in the morning following 12 weeks of intervention. Linear speed was assessed using a 50-meter sprint test, CoDs were measured using the Illinois agility test (IAT), and lower-body explosive power was evaluated through CMJ performance using a Vertec measuring device. Detailed descriptions of all tests are presented in the supplementary appendix. 1. All performance tests demonstrated excellent test–retest reliability, including the 50-m sprint, IAT, CMJ, TST, and CRSL (Table 4).

Statistical analysisThe sample size for the present study was estimated using G*Power version 3.1.9.6,34 developed by Franz Faul at the University of Kiel, Germany. An a priori power analysis was performed for a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a within–between interaction, based on the following parameters: an alpha level of 0.05, a statistical power (1–β) of 0.80, a non-sphericity correction of 1, a correlation between repeated measures of 0.50, and a medium effect size (f = 0.25).35 The power analysis indicated that a minimum of 42 players was required to achieve statistical power. To account for potential dropouts (6.33 %), a total of 45 field hockey players were enrolled in the study.

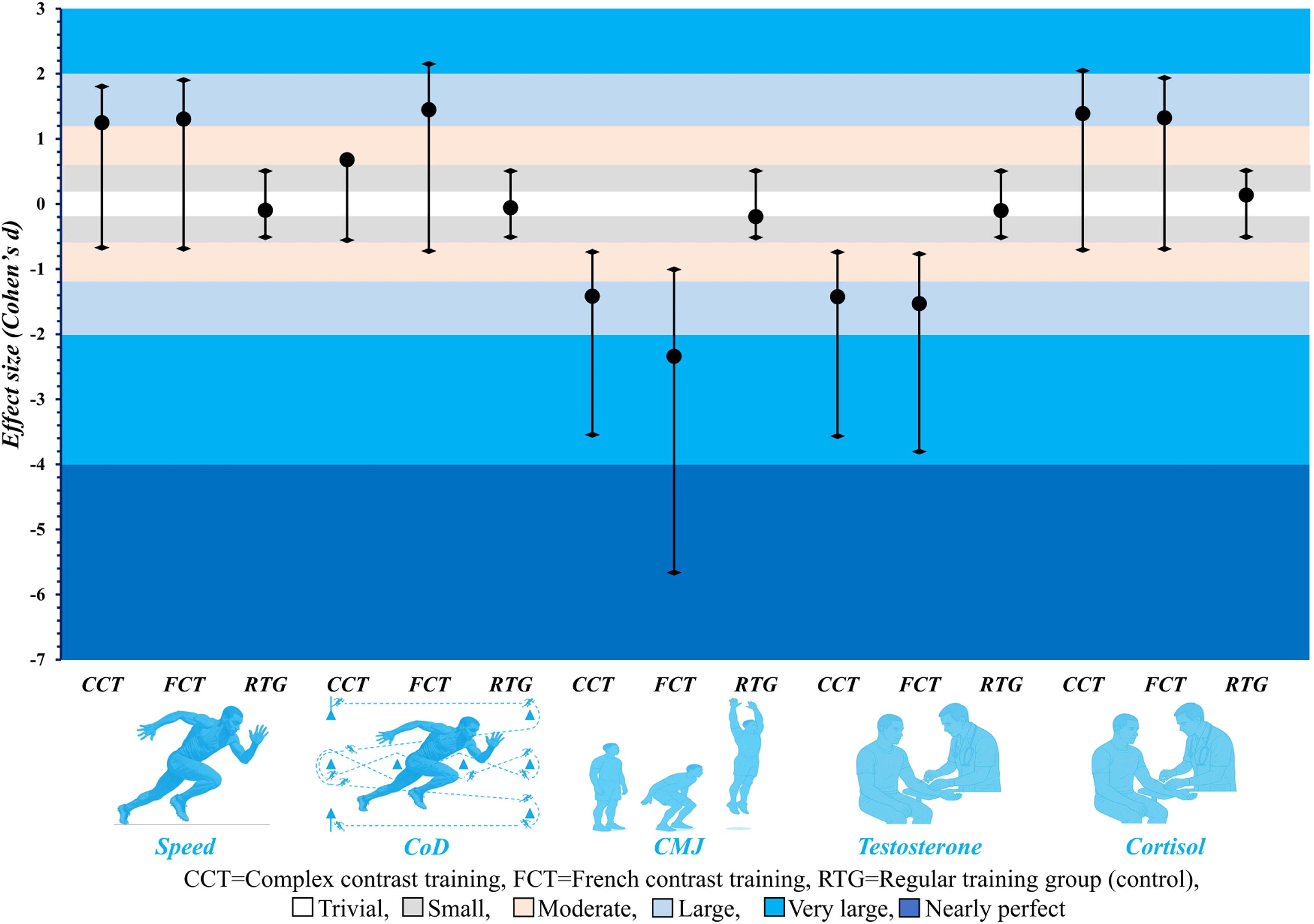

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 27.0, with the level of significance set at p < 0.05. Data were initially tabulated using Microsoft Excel, and the Shapiro–Wilk test was conducted to assess the normality of the distributions. Baseline characteristics, including age, weight, stature, and BMI, were analyzed using one-way ANOVA to identify any pre-existing differences among the three groups (CCT, FCT, and RTG), with Levene's test used to confirm homogeneity of variances.36 The reliability of the outcome measures was assessed through intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs). Specifically, ICCs were used to evaluate test–retest reliability within the RTG group (for 10 field hockey players).37 Inter-rater reliability across trials and assessors was also determined and interpreted as follows: excellent (>0.90), good (0.75–0.90), moderate (0.50–0.75), and poor (<0.50).38 To examine within-group changes from A1 to A2 across all outcome measures, paired sample t-tests were applied. The magnitude of these changes was further quantified using Cohen's d, categorized as: trivial (0–0.20), small (0.21–0.60), moderate (0.61–1.20), large (1.21–2.0), very large (2.01–4.0), and nearly perfect (>4.0).39 A repeated measures ANOVA was employed to assess the effects of time (AI vs A2), group (CCT, FCT, RTG), and the interaction between time and group (time × group) on all outcome variables. In addition, separate repeated measures ANOVA tests were conducted within each individual group to evaluate the between-group effects over time. Post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni correction was performed to locate specific group differences. Effect sizes were reported using eta squared (η²), interpreted as small (≤0.06), medium (0.06–0.14), and large (≥0.14), providing insight into the practical significance of the observed effects.40

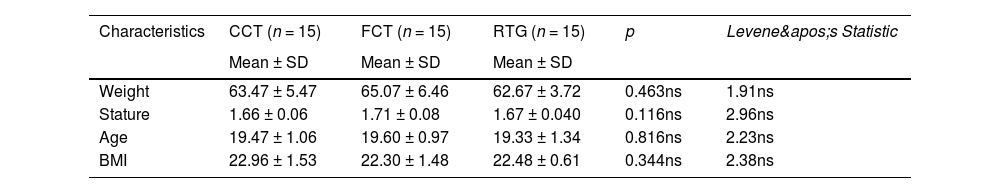

ResultsThe baseline characteristics (through A1 assessment) of the two intervention groups (CCT and FCT) and the RTG are presented in Table 3. No significant differences were observed among the groups.

Baseline characteristics of participants and Levene's Statistic.

CCT: Complex-contrast training group; FCT: French contrast training group; RTG: Regular training group (control group); ns: No significant differences.

Table 4 presented that the ICCs for the evaluated tests (Speed, CoDs, CMJ, TST, and CRSL) ranged from 0.97 to 0.99, while the coefficients of variation (CV) for the evaluated tests (Speed, CoDs, and CMJ) ranged from 4.7 to 7 %.

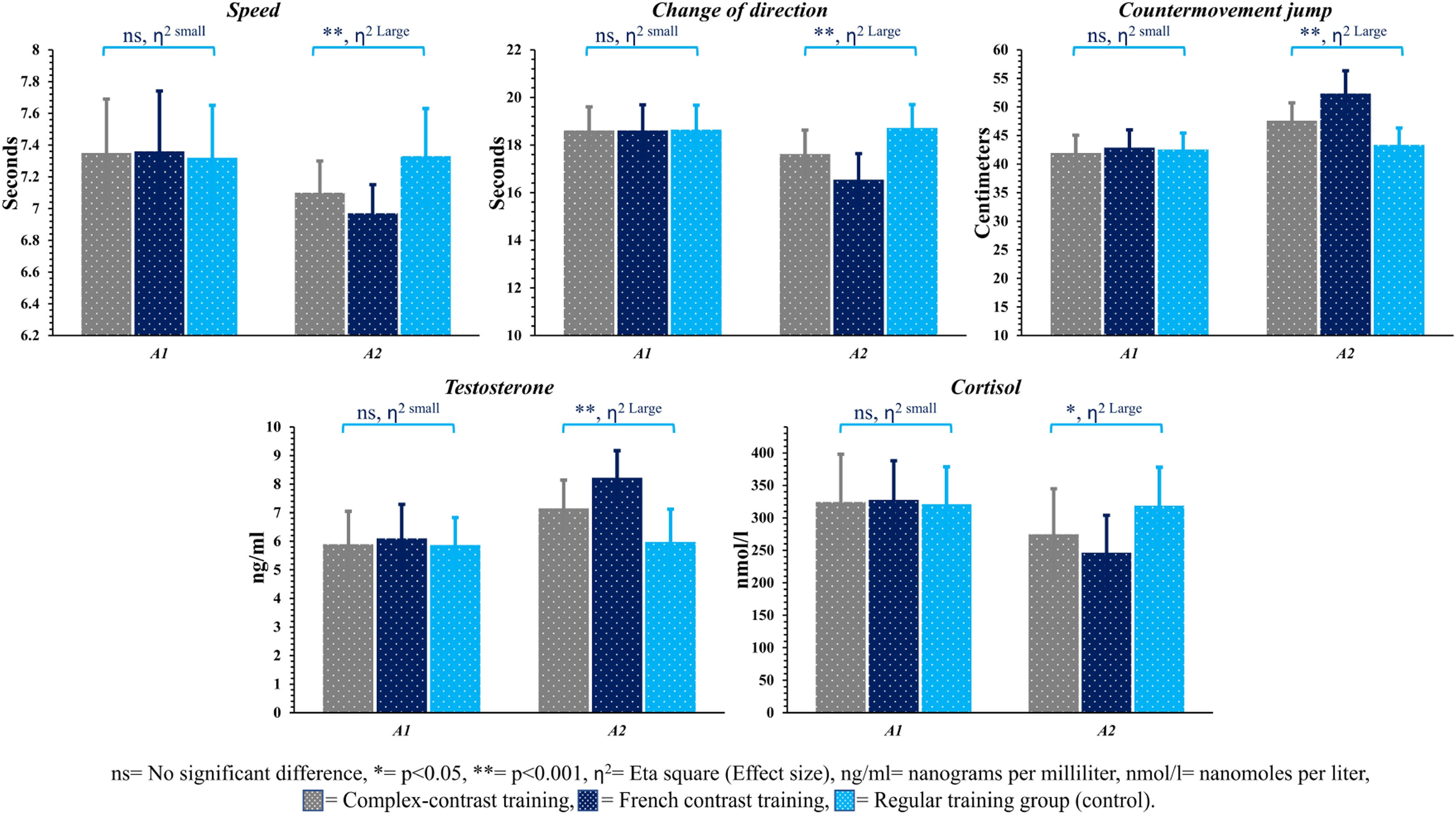

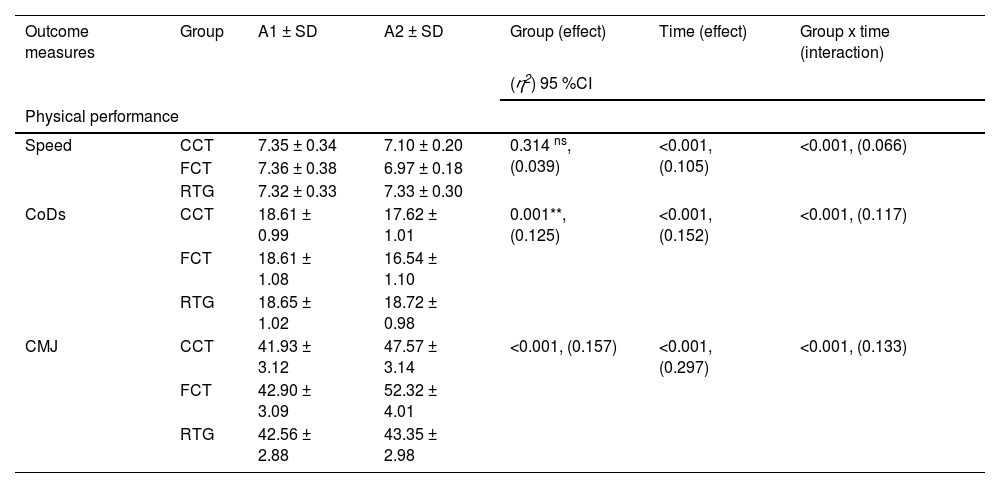

Table 5 presents the repeated-measures ANOVA results for speed, CoDs, CMJ, TST, and CRSL over two time points x three groups. Speed showed significant changes over time (η²=moderate) and for the group × time interaction (η²=moderate), but not between groups (η²=small). CoDs demonstrated significant effects for between-group (η² =moderate), time (η²=large), and group × time (η²=moderate). CMJ showed large effects for between-group (η²=large), time (η²=large), and a moderate effect for between-group × time (η²=moderate). TST showed significant effects for between-group (η²=moderate), time (η²=large), and group × time (η²=moderate). CRSL showed significant effects for between-time (η²=moderate) and group × time (η²=small), with no between-group differences (η²=small).

Repeated measures analysis of variance.

A1: Baseline assessment; A2: 12-week assessment; CoDs: Change of direction speed; CMJ: Countermovement jump; TST: Testosterone; CRSL: cortisol; CCT: Complex- contrast training; FCT: French contrast training; RTG: Regular training group (control group); ⴄ2: Eta square; **: Significant at 0.01; ns: No significant differences.

Based on the paired-sample t-test results and cohen's d presented in Fig. 2, both the CCT and FCT groups showed significant improvements in speed, CoDs, CMJ performance, TST, and CRSL from A1 to A2 (p < 0.05-p < 0.001, d=trivial-very large). In contrast, the RTG did not show any significant improvement in any of the performance variables across the same period.

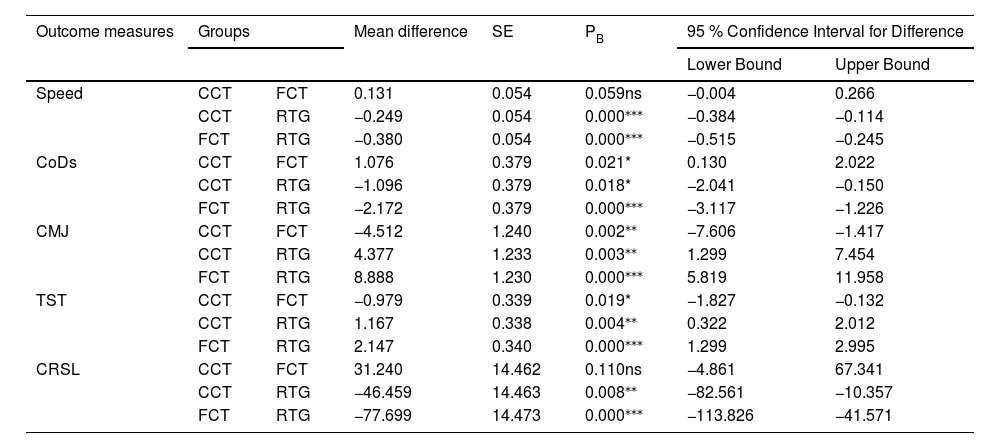

Fig. 3 illustrates that the one-way ANOVA results for the A1 assessment showed no differences across groups at the 0.05 level, whereas the A2 assessment indicated enhancements in speed, CoDs, CMJ, TST, and CRSL in both training intervention groups (CCT and FCT). The Bonferroni post hoc test presented in Table 6 revealed that the FCT group demonstrated greater improvements in CoDs, CMJ, and TST compared with the CCT group. Speed and CRSL had a higher mean difference in FCT and RTG (speedMD =−0.380, CRSLMD =−77.699). And CCT and FCT groups had significantly higher improvement in speed, CoDs, CMJ, TST, and CRSL at p < 0.05-p < 0.001 levels.

Bonferroni post hoc comparison.

| Outcome measures | Groups | Mean difference | SE | PB | 95 % Confidence Interval for Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Speed | CCT | FCT | 0.131 | 0.054 | 0.059ns | −0.004 | 0.266 |

| CCT | RTG | −0.249 | 0.054 | 0.000⁎⁎⁎ | −0.384 | −0.114 | |

| FCT | RTG | −0.380 | 0.054 | 0.000⁎⁎⁎ | −0.515 | −0.245 | |

| CoDs | CCT | FCT | 1.076 | 0.379 | 0.021* | 0.130 | 2.022 |

| CCT | RTG | −1.096 | 0.379 | 0.018* | −2.041 | −0.150 | |

| FCT | RTG | −2.172 | 0.379 | 0.000⁎⁎⁎ | −3.117 | −1.226 | |

| CMJ | CCT | FCT | −4.512 | 1.240 | 0.002⁎⁎ | −7.606 | −1.417 |

| CCT | RTG | 4.377 | 1.233 | 0.003⁎⁎ | 1.299 | 7.454 | |

| FCT | RTG | 8.888 | 1.230 | 0.000⁎⁎⁎ | 5.819 | 11.958 | |

| TST | CCT | FCT | −0.979 | 0.339 | 0.019* | −1.827 | −0.132 |

| CCT | RTG | 1.167 | 0.338 | 0.004⁎⁎ | 0.322 | 2.012 | |

| FCT | RTG | 2.147 | 0.340 | 0.000⁎⁎⁎ | 1.299 | 2.995 | |

| CRSL | CCT | FCT | 31.240 | 14.462 | 0.110ns | −4.861 | 67.341 |

| CCT | RTG | −46.459 | 14.463 | 0.008⁎⁎ | −82.561 | −10.357 | |

| FCT | RTG | −77.699 | 14.473 | 0.000⁎⁎⁎ | −113.826 | −41.571 | |

ns: No significant differences.

The present RCT evaluated the comparative effects of CCT and FCT against an RTG on physical performance measures and steroid hormones in tier 3 male field hockey players over 12 weeks. Both CCT and FCT induced significant improvements in speed, CoDs, CMJ, TST, and CRSL, while the RTG group did not show meaningful changes in any outcome variable. Notably, FCT elicited greater improvements in CoDs, CMJ, and TST compared to CCT, whereas both training interventions demonstrated similar gains in speed and reductions in CRSL. These findings indicate that both training modalities are effective in enhancing performance and hormonal profiles, with FCT offering certain advantages in explosive and agility-based performance parameters. The present findings are consistent with existing literature reporting that contrast training methods, which integrate high-load resistance work with plyometric or ballistic movements, are highly effective for improving neuromuscular performance in team sport athletes.41 Previous studies in soccer, rugby, and basketball have shown significant gains in vertical jump height, sprint performance, and agility after 6–12 weeks of contrast training.15,16,26,27 Our CMJ improvement magnitudes (CCT:+5.64 cm; FCT:+9.42 cm) are comparable to those reported by Hammami et al.,27 who found 8–10 cm gains following 8 weeks of contrast training in junior athletes. The consistency of these findings reinforces the transferability of contrast-based protocols across different sport populations.

Regarding CoDs, our findings agree with Hammami et al.,41 who explored that contrast and plyometric-based programs enhance eccentric strength and braking efficiency, leading to faster directional changes. The superior CoDs improvements in FCT may be attributed to its unique structure, combining heavy resistance, plyometric, assisted plyometric, and ballistic exercises within a single cluster.28 This sequential force-velocity exposure may provide a more comprehensive neuromuscular stimulus conducive to multidirectional sport demands. Hormonal adaptations observed in this study align with existing literature showing that structured resistance and plyometric training can increase TST while reducing CRSL.23,42,43 Increased TST facilitates muscle hypertrophy, power development, and tissue recovery, whereas lower CRSL attenuates catabolic activity.44,45 The greater elevation of TST in the FCT group (+2.12 nmol/L) compared to CCT (+1.25 nmol/L) may be attributed to the greater neuromuscular stress and velocity exposure associated with the assisted plyometric component. Such hormonal responses suggest enhanced readiness for high-intensity performance and positive long-term adaptation. The likely mechanisms underpinning performance improvements in both groups include PAPE, neuromuscular facilitation, and enhanced stretch-shortening cycle efficiency.21,46 Both CCT and FCT incorporate heavy-load priming followed by explosive movements, which enhances motor-unit recruitment and contractile efficiency.9,47 The FCT method, through assisted plyometrics, may further increase high-threshold motor-unit engagement, promoting faster force production.9,48 These adaptations contribute to an enhanced rate of force development, stretch–shortening cycle efficiency, and ultimately better performance in explosive and agility tasks.49

Speed improvements in both intervention groups are consistent with previous sprint-training studies demonstrating enhanced force application during acceleration and increased neural efficiency.50 The comparable sprint improvements between CCT and FCT suggest that both methods sufficiently stimulate mechanisms associated with acceleration performance. From a practical standpoint, both CCT and FCT may be effective for sprint-development phases during pre-season preparation in field hockey. The superior outcomes for FCT in CoDs, CMJ, and TST may be explained by its broader range of force–velocity targeting within a single training session. The sequence of heavy resistance, plyometric, assisted plyometric, and ballistic exercises in FCT offers varied yet complementary neuromuscular stimuli.17 This approach may not only enhance physical output but also improve motor learning and transferability to sport-specific actions.9 Additionally, the greater variability in exercise selection and intensity could reduce monotony and maintain higher levels of engagement and motivation, which may indirectly influence hormonal responses.24

Limitations and future directionsSeveral limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The sample consisted exclusively of tier 3 male field hockey players, limiting generalization to elite, youth, or female athletes. The sample size, while sufficient for statistical significance, may not have captured more subtle between-group differences. Hormonal measurements were collected at rest, and future studies could assess acute post-exercise responses to better understand the temporal patterns of endocrine adaptations. Additionally, follow-up assessments during the competitive season would help determine the retention of training-induced gains under match-play conditions. Future research could explore the effects of contrast training methods across different phases of the competitive calendar, their interaction with sport-specific conditioning drills, and the integration of neuromuscular assessments such as electromyography or force–velocity profiling to further clarify underlying mechanisms. Comparisons between contrast training and other advanced resistance training methods, such as velocity-based training or accentuated eccentric loading, could also provide valuable insights into optimizing performance for field hockey and other team sports.

Practical applicationFrom a practical standpoint, these findings indicate that strength and conditioning coaches should incorporate both CCT and FCT in field hockey training. FCT may be prioritized when maximizing explosive power, change-of-direction ability, and favorable hormonal responses is desired, particularly when equipment for assisted plyometrics is available. CCT remains a highly effective and accessible alternative when resources are limited, still delivering meaningful neuromuscular gains. The structured progression and familiarization phase used in this study demonstrate a safe and effective model for implementing contrast-based programs, supporting improved performance while minimizing fatigue and maintaining hormonal balance in competitive athletes.

ConclusionThis study demonstrates that both CCT and FCT are effective in enhancing speed, CoDs, CMJ, TST, and CRSL profiles in tier 3 male field hockey players over a 12-week intervention. While both methods outperformed RTG, FCT offered greater improvements in CoDs, CMJ, and TST, likely due to its broader neuromuscular stimulus and greater velocity exposure. These findings support the application of contrast training modalities as part of an integrated strength and conditioning program, with FCT being particularly advantageous for maximizing explosive performance and favourable hormonal adaptations in competitive field hockey players.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologiesGenerative AI tools were utilized solely to assist with visual organization and minor language refinement. All AI-assisted outputs were thoroughly reviewed, verified, and refined by the authors, who take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript. No copyrighted or third-party materials were used.

Ethical statementEthical clearance and informed consent were obtained prior to the start of the study. The study received approval from the institutional ethical committee at Pondicherry University (Approval No HEC/PU/2023/05/07–08–2023). Written/verbal informed consent was taken from all participants. The study was carried out in accordance with the principles enunciated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

FundingThe current study received no external funding.

With regard to the research, authorship, and publication of this article, the authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest.

All participants of the study deserve our sincere thanks for committing so much of their time and effort to this research.