Historically, research in exercise physiology has tended to overlook women, focusing mostly on studies involving men and disregarding female hormonal variations, including the effects of commonly used hormonal contraceptives among athletes. The influence of exogenous hormones could affect health and athletic performance, besides providing a stable hormonal environment to assess the acute effects of sexual hormones on physiological variables and performance. These potential impacts are critical to guide training strategies for female athletes.

HypothesisHormonal contraceptives affect physiological responses and athletic performance in healthy young women and elite athletes. It is hypothesized that during the inactive phase, aerobic and anaerobic exercise, as well as strength, would be superior compared to the active phase.

Materials and MethodsLongitudinal observational study with repeated measures exploring physiological responses in five elite athletes, all using hormonal contraceptives. Variables including lactate, heart rate, and power output were evaluated during a submaximal 2000-meter rowing ergometer test, assessed during two phases of the contraceptive cycle. Results: Baseline characteristics were described. No significant differences were observed in physiological variables between the two phases of the hormonal contraceptive cycle.

ConclusionsThere were no significant differences in performance between active and inactive phases of hormonal contraceptives. Variations in physiological parameters among studies suggest the need for an individualized approach. Future studies should use larger samples and rigorous methodologies to clarify effects of the contraceptive use on athletes.

Historically, research in physiology and sports performance has exhibited a marked bias towards the male population, both in study design and in the interpretation and application of results. This approach has relegated the biological specificities and needs of women to the background, perpetuating a significant gap in scientific knowledge. In the field of female physiology, research has been largely limited to reproductive aspects, overlooking the essential role of ovarian hormones in multiple physiological processes. The inclusion of women as study participants has been scarce, and in many cases, methodologies designed for men have been applied, thus rendering the particularities of female physiology invisible.1-3 In the few studies that include women in sports research, their specific hormonal variations are often overlooked, or testing is conducted during times of low hormonal levels to avoid potential interference.3,4

The natural fluctuations in the blood concentrations of the two female hormones, estrogen and progesterone, are essential for regulating the menstrual cycle (MC) and maintaining reproductive health. Estrogen, produced mainly in the ovaries, regulates the MC, secondary sexual development, and bone density.5,6 Progesterone, in addition to being crucial for reproduction, influences the nervous and immune systems and serves as a precursor to other steroid hormones.7 Both hormones affect mood, cognition, metabolism, and overall health throughout a woman's life.7 These natural fluctuations are under the control of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which are produced by the pituitary gland. FSH and LH blood concentrations are also cyclic, playing a key role in fertility, regulating the MC, ovulation processes, and estrogen production.8

Eumenorrhea refers to the presence of regular MC, indicative of a healthy hormonal and reproductive system.9 Methodologically, it is defined by cycles of 21–35 days, an LH surge, an appropriate hormonal profile, and the absence of hormonal contraceptives (HC) in the last three months.10 Menstrual irregularities, such as amenorrhea, an abnormal absence of menstruation, and particularly functional hypothalamic amenorrhea, are common in athletes and are often associated with the relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs) syndrome. .11–13 In athletes, amenorrhea is linked to hypothalamic hormonal changes that reduce LH pulsatility, suppress ovarian steroids, and maintain the pituitary response to Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) .14

To address and manage these various menstrual irregularities, many women turn to HCs. These not only provide effective birth control but also offer significant benefits in regulating the MC and mitigating symptoms related to menstrual disorders. There are various HC administration methods, such as oral contraceptives (OCs), implants, injections, transdermal patches, vaginal rings, and intrauterine systems.15 A recent study with 430 female elite athletes revealed that 213 were using HCs, indicating that almost half did not present an eumenorrheic MC. Of these athletes, 145 (68 %) used OCs, making this the most common hormonal method.16 OCs can be combined (estrogen and progestin) or progestin-only, and are available in monophasic, biphasic, or triphasic formulations, with different hormonal combinations that affect the physiological response.16,17 The variability in the type and concentration of estrogen and progestin among different contraceptive preparations can significantly influence the body’s physiological response.16 OCs operate through a negative feedback mechanism on the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, inhibiting the secretion of FSH, LH, and GnRH, thereby suppressing ovulation.18,19

Despite the high prevalence of OC use among athletes, there is a notable lack of research examining the effect of hormonal fluctuations within the OC use cycle on women's exercise responses.20 Most of the current literature has focused on evaluating physiological differences between OC users and non-users, or responses before and after starting their use.17 Furthermore, many athletes have adopted the strategic use of OCs to modulate or even eliminate menstrual bleeding, valuing the reliability and reversibility of contraception, along with the ability to mitigate the symptoms of a regular MC.18,21

Currently, the lack of high-quality data limits understanding of how hormonal variations from the MC or HC use influence exercise physiology,9,18,22,23 due to methodological issues such as inadequate menstrual phase verification, small sample sizes, and high intra- and interindividual variability. Although HCs could offer a more stable hormonal environment for investigating these relationships, most studies compare users and non-users without analyzing the phases of the use cycle.16 Current research suggests that aerobic performance, anaerobic performance, and strength may vary throughout the HC use cycle. Therefore, it is essential to conduct studies that analyze these variables in greater detail, using HCs as a framework to obtain more consistent and applicable results in the sports field.17 A deeper understanding of these effects is not only crucial for the development of strategies that promote athletes’ health and well-being but also for optimizing their sports performance. Addressing this research gap will allow for evidence-based recommendations, thereby improving athletes' ability to effectively manage their training and competition regimes according to their hormonal profiles. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the influence of hormonal contraceptives on physiological responses and athletic performance in healthy young women and elite female athletes, comparing the effects during the active and non-active phases of hormonal contraceptive use. It was hypothesized that HC could significantly affect physiological responses and athletic performance, with superior outcomes expected during the non-hormonally active phase (NHAP) compared to the hormonally active phase (HAP). This difference is attributed to hormonal variations induced by contraceptive use, which alter the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and, consequently, impact energy metabolism and muscle contractility—, especially in high-demand physical contexts.18,24,25

Materials and methodsEthical approvalTo ensure the personal data protection and rights of participants, the study complied with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, the Nuremberg Code, and the Belmont Report, as well as following applicable national and regional regulations. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of the Catalan Sports Council (029/CEICGC/2023), and informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study.

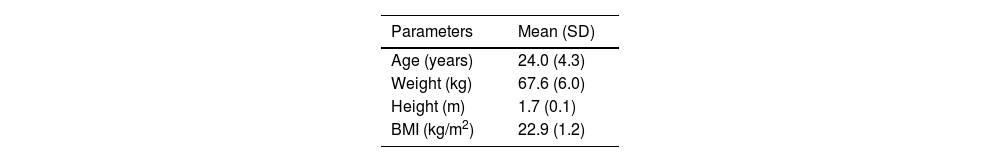

ParticipantsThis study employed a longitudinal observational design with repeated measures to examine changes and trends in specific variables over time, without any active intervention. The target population consisted of elite female rowers, over 18 years old, federated, in reproductive age, who were using HC, specifically oral contraceptives or vaginal rings. The baseline characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

The inclusion criteria for participation in the study were the use of any type of HC for 3 months or more, and the alteration of the endogenous hormonal profile by these contraceptives. The exclusion criteria included the use of non-hormonal contraceptive methods or methods that had a hormonal profile different from that generated by the HC used. To identify potential participants who met the inclusion criteria, an initial assessment of medical records and information provided by the participants themselves was conducted. Women who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study and were provided with detailed information about the objectives, procedures, and potential risks involved.

The sampling method was non-probabilistic and consecutive, selecting participants who met the established criteria, with informed consent obtained during an in-person appointment. We did not implement any random allocation procedure, as there was no assignment to treatment groups. However, the order of testing across the active and inactive phases of the contraceptive cycle was randomized to minimize potential order effects. No formal sample size calculation was performed due to resource limitations and the inability to expand the sample. The study was open-label, with no blinding at any level, as both the participants and researchers were aware of the ongoing study.

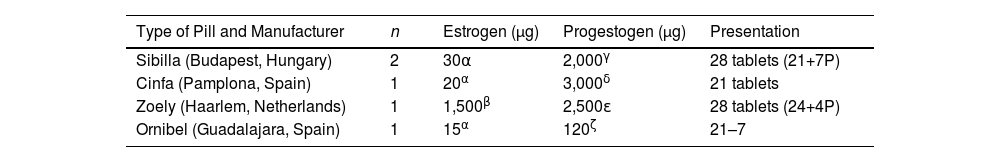

Hormonal profileRegarding the HC preparations used by the participants, a variety of products were observed in the study. Two participants used a pill containing 30 µg of the estrogen ethinylestradiol and 2000 µg of the progestogen dienogest, presented as a 28-pill cycle, of which 21 are active pills and 7 are placebos. One participant used a pill containing 20 µg of the estrogen ethinylestradiol and 3000 µg of the progestogen drospirenone, presented as 21 active daily pills and 7 days of rest. Another participant used a pill containing 1500 µg of the estrogen estradiol and 2500 µg of the progestogen nomegestrol acetate, presented in a 28-pill cycle with 24 active pills and 4 placebos. Lastly, one participant used a vaginal contraceptive ring that contains 15 µg of the estrogen ethinylestradiol and 120 µg of the progestogen etonogestrel. This ring is used for 21 days, followed by 7 days without use to restart the cycle. These differences in HC preparations are presented in Table 2 and may have implications for the participants' physiological responses and sports performance.

Characteristics of the hormonal contraceptives used by the participants.

Note. Type of synthetic hormonal compound: α Ethinylestradiol; β Estradiol; γ Dienogest; δ Drospirenone; ε Nomegestrol acetate; ζ Etonogestrel. Abbreviations: n: sample size; μg: micrograms; comp: tablets; P: placebo.

To assess the influence of HC use on the physical performance of female athletes, a submaximal 2000-meter test was conducted on a Concept2 rowing ergometer (Concept2, Morrisville, USA). This test was designed to evaluate physiological parameters related to aerobic-anaerobic capacity and rowing efficiency under controlled conditions. The protocol consisted of covering a distance of 2000 m in approximately 7 min at a constant intensity, maintaining a stroke rate of 28 strokes per minute. Participants were instructed to refrain from alcohol consumption and to follow a balanced diet, ensuring they were well-nourished and hydrated prior to the test.

Before the performance assessments, participants were familiarized with the rowing ergometer, the experimental setting, and the procedures for lactate sampling and heart rate (HR) monitoring. As they regularly used the rowing ergometer during training, they were already familiar with the equipment. The submaximal tests were carried out at two specialized high-performance centers: the Centre Especialitzat de Tecnificació Esportiva de Rem in Banyoles (Girona, Spain), and the Centro Especializado de Alto Rendimiento de Remo y Piragüismo y Residencia de Deportistas in Sevilla (Spain), under the supervision of rowing technical specialists. Data collection was conducted at two different time points: during the HAP, between days 12 and 20 of the cycle, and during the NHAP, between days 1 and 7.26 For lactate measurements, a capillary blood sample was taken from the earlobe using a portable lactate analyzer before the start of the test (Pre-Lactate) of the test and one minute after its completion (Post-Lactate). The device used for measurement was the Lactate Scout +Plus (Scout +Plus, Cardiff, United Kingdom). HR was continuously recorded throughout the test the participants’ personal heart rate monitors, obtaining both mean and maximum HR values. Power output was measured directly by the rowing ergometer and expressed in watts (W); the mean power output generated during the 2000 m was recorded using the Concept2 ergometer. Hormonal profile data were self-reported by the athletes using the mobile application FitrWoman, a scientifically validated tool that allows for detailed tracking of the menstrual cycle, symptoms, and other aspects related to hormonal health and athletic performance. Evaluators compiled the lactate, HR, and power data in spreadsheets shared via an online platform, and the principal investigator later downloaded the data to perform the statistical analysis.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed using R software, with a significance level of 0.05 for the intention-to-treat analysis. Quantitative variables were described using measures of central tendency and dispersion, and normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test (p > 0.05 indicating normality). Comparison between contraceptive cycle phases was conducted using the paired samples Student’s t-test, calculating the mean difference with a 95 % confidence interval. In addition, linear mixed models were employed to analyze the effects of the cycle phases, incorporating random effects to address inter-subject variability and the dependence of repeated observations, allowing for precise estimates of effects and enhancing the validity of the analysis. In our study, with a sample size of n = 5, Cohen’s d was used to compare the magnitude of effects in a standardized manner, considering d ≈ 0.2 as small, d ≈ 0.5 as medium, and d ≈ 0.8 as large. This approach helped determine the sample size needed to detect significant effects with greater statistical confidence.

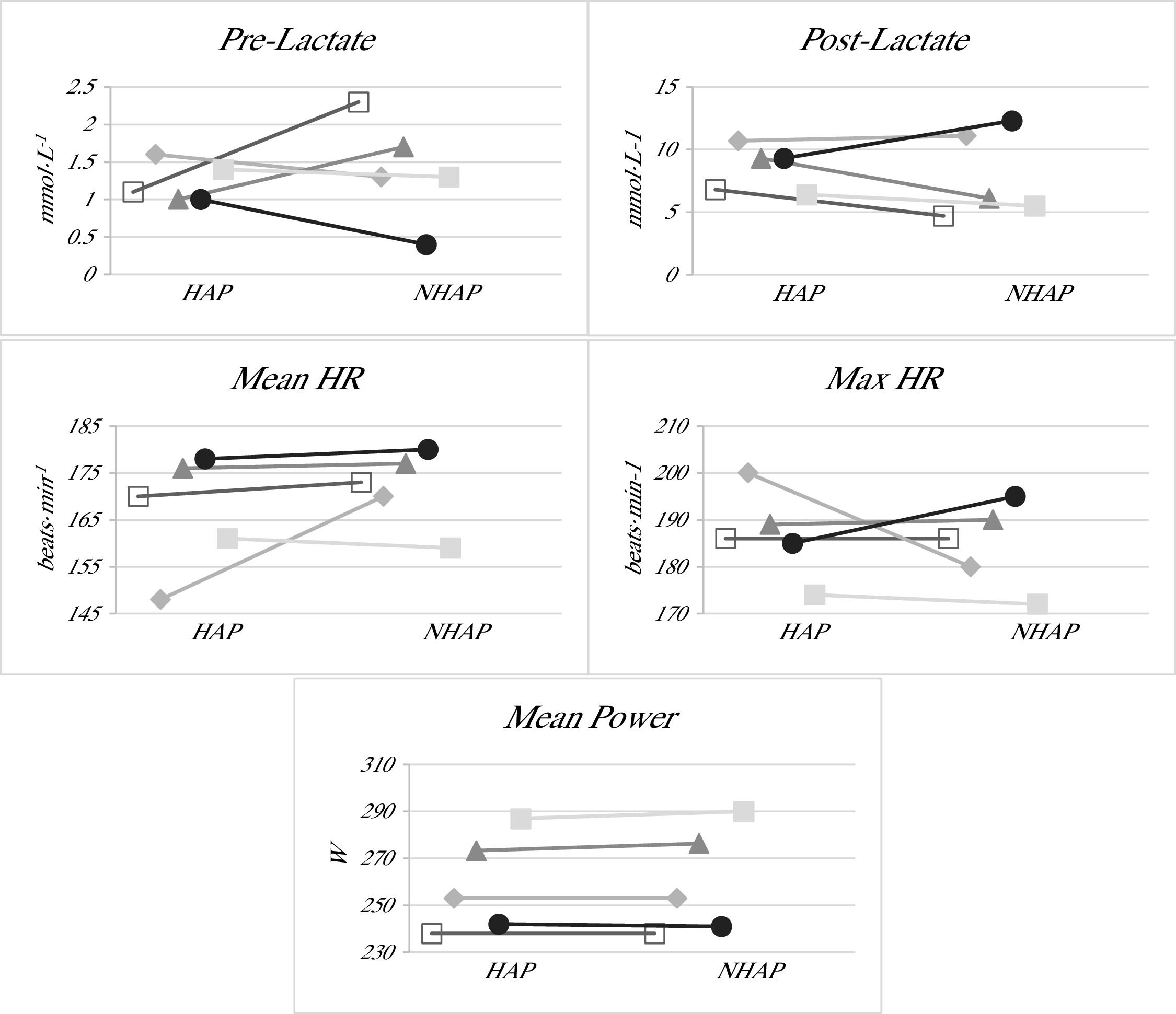

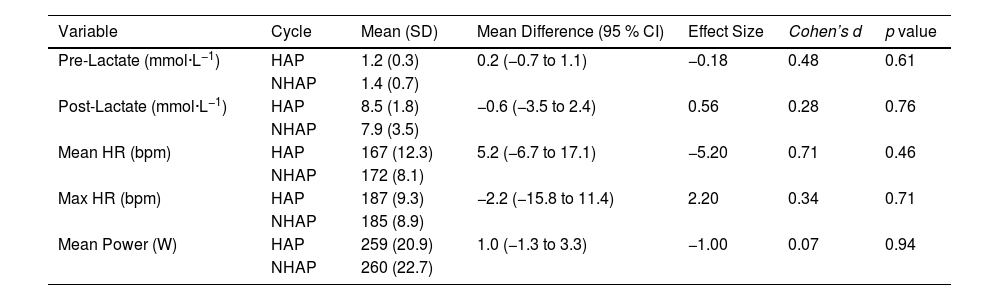

ResultsTo evaluate the effect at the two moments of the HC cycle, HAP and NHAP, five physiological variables were analyzed: Pre-Lactate, Post-Lactate, Mean HR, Max HR, and Mean Power. These variables were evaluated through a submaximal performance test, allowing analysis of both pre and post-test values, as well as the mean and maximum values from the tests performed. The detailed results of each variable and their comparison between the two cycle moments are presented below, in Table 3.

Comparison of lactate levels, heart rate, and power between the Hormonally active phase (HAP) non-hormonally active phase (NHAP).

Note. The values are presented as mean (standard deviation), mean difference (95 % confidence interval), effect size, Cohen's d, and p value. Abbreviations: HAP: Hormonally Active Phase; NHAP: Non-Hormonally Active Phase; L: Liters; bpm: beats per minute; W: Watts; SD: Standard Deviation; CI: Confidence Interval.

In the analysis of Pre-Lactate, a mean of 1.2 (0.3) mmol·L−1 was observed for HAP and 1.4 (0.7) mmol·L−1 for NHAP. The mean difference between the two phases was 0.2 mmol·L−1 (-0.8 to 1.1), with a p-value of 0.61 and a moderate effect size (d ≈ 0.48). Regarding Post-Lactate, the mean was 8.5 (1.8) mmol·L−1 for HAP and 7.9 (3.5) mmol·L−1 for NHAP. The mean difference was −0.6 mmol·L−1 (-3.5 to 2.4), with a p-value of 0.76, and a small effect size (d ≈ 0.28). For Mean HR, a mean of 167 beats·min−1 (12.3) was recorded for HAP and 172 beats·min−1 (8.11) for NHAP, with a mean difference of 5.2 beats·min−1 (−6.7 to 17.1) and a p-value of 0.46, and a considerable effect size (d ≈ 0.71). For Max HR, the mean was 187 beats·min−1 (9.3) for HAP and 185 beats·min−1 (8.9) for NHAP, with a mean difference of −2.2 beats·min−1 (−15.8 to 11.4) and a p-value of 0.71, and a small effect size (d ≈ 0.34). Finally, for Mean Power, a mean of 259 W (20.9) was recorded for HAP and 260 W (22.7) for NHAP, with a mean difference of 1.0 W (−1.3 to 3.3) and a p-value of 0.94, and a very small effect size (d ≈ 0.07). None of the comparisons between variables reached a p-value < 0.05; consequently, no significant differences were found between HAP and NHAP. These results highlight the importance of considering both statistical significance and effect size to properly interpret findings.

In Fig. 1, the individual lines for each participant can be visualized, allowing for the observation of trends in each of the study variables between the active and non-active (placebo) phases. This representation makes it possible to identify whether there is a general trend in the subjects’ responses or if any participant shows a markedly different evolution compared to the rest. Thus, the figure facilitates the detection of potential individual patterns or outlier cases in the evolution of the physiological variables analyzed.

Individual comparison of physiological parameters between the HAP and the NHAP.

Note. The values shown correspond to the individual lines of each study participant at the two evaluation points for the different variables analyzed: Pre-Lactate, Post-Lactate, mean heart rate (Mean HR), maximum heart rate (Max HR), and Mean Power. Each line connects the measurements corresponding to each subject in the hormonally active phase (HAP) and the non-hormonally active phase (NHAP).

Finally, considering the small sample size of n = 5, the use of Cohen’s d is particularly valuable, as it provides standardized measure of effect magnitude. This can guide the interpretation of results beyond statistical significance and inform future research by helping to estimate the potential physiological impact and the sample size required to detect meaningful differences in similar studies.

DiscussionThe present research aimed to examine the influence of HC on physiological responses and sports performance in healthy young women and elite athletes, comparing the effects during the HAP and the NHAP. This study did not identify any physiologically significant differences in the parameters reflecting performance in a submaximal 2000-meter rowing ergometer test between the phases of the HC cycle. Our findings refute the proposed hypothesis that, during the NHAP, aerobic capacity, anaerobic power, and strength would be superior compared to the HAP in elite rowing athletes.

To compare the results of the present study with others, we considered the test or effort performed as aerobic-anaerobic due to the combination of duration, intensity, and observed lactate levels. Both energy systems are contributing significantly to completing the test. In this regard, some authors have shown that anaerobic power is affected by the phase of the HC cycle.27,28 These suggest that athletes who depend on the stretch-shortening cycle, such as jumpers and sprinters, could benefit from competing during HAP. However, the improvement in reactive strength performance during this phase remains poorly explained.28 Some studies have confirmed that estrogen levels can alter metabolism during acute exercise.29,30 An increase in estrogen concentration inhibits gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, which spares glycogen and increases the use of lipids as an energy source.29 On the other hand, in these modalities, some authors observed a reduction in peak blood lactate and an increase in pH during the NHAP (when progestogen is lower) compared to the HAP.29,31 Supporting this, recent studies showed that blood lactate was higher in the HAP compared to the NHAP,32,33 findings consistent with our results, though not statistically significant, but with a potential moderate/high size effect according to Cohen’s d. However, despite the statistical analysis, the physiological relevance of a 1 mmol/L change in blood lactate is likely minimal and could fall within the typical margin of error for this variable.32 This explanation of the difference in lactate values according to the cycle phase suggests that blood lactate may be influenced by factors such as buffering capacity and plasma volume, rather than changes in substrate metabolism due to variations in estrogen levels. An increase in circulating aldosterone during the NHAP could improve fluid and electrolyte retention, increasing plasma volume and buffering capacity. In short-duration and high-intensity efforts, exogenous steroids may not have sufficient time to significantly influence substrate metabolism or buffering capacity.29 In summary, current scientific evidence does not support a direct relationship between the phases of the HC cycle and blood lactate concentrations in anaerobic exercise.

On the other hand, regarding aerobic exercise, early authors investigating the effects of HC suggested that they negatively affected exercise performance and V̇O2max.34,35 Additionally, a longitudinal study reported a reduction in V̇O2max in moderately trained women after four months of using triphasic OC.24 However, more recently, other studies have demonstrated no differences in aerobic performance across different phases of the OC cycle in rowers33,36 and other sport modalities.37 Likewise, no statistically significant variations in blood lactate concentrations after exercise between these phases were observed.33 In addition, HR, pulmonary ventilation, and V̇O2 during aerobic endurance tests were not significantly affected by the hormonal cycle phase,33,34 findings that align with our results for average and maximum HR, although they were not statistically significant. Our findings point to metabolic and cardiorespiratory stability during aerobic exercise regardless of hormonal fluctuations due to HC use, and agree with recent reports studying oral contraceptive pills38 and the natural menstrual cycle.39

ConclusionsThe present study analyzed the influence of HC on physiological responses and sports performance in healthy young women and elite rowing athletes. Our results did not reveal physiologically significant differences in performance parameters during NHAP compared to HAP. While some previous studies reported varying results, these discrepancies may be attributed to differences in the type of exercise, its duration and intensity, the performance level of the participants, and the type of HC used.

The main limitations of this study include the small sample size and the heterogeneity in the composition of contraceptives, as well as the lack of complete blinding and insufficient control of external factors such as diet and participants' mood, which may have introduced some degree of uncontrolled bias and affected the validity of the results. From a practical perspective, since the observed effects were mostly trivial and variable, no general recommendation can be made regarding the use or discontinuation of HC, highlighting the need for an individualized approach. To draw more definitive conclusions, future studies should focus on larger sample sizes and adopt randomized controlled longitudinal designs, which would allow for a more robust examination of the unresolved questions surrounding the effects of HC on athletic performance.

The Authors declare that they don't have any conflict of interests

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the athletes who participated in this study for their commitment, effort, and valuable contribution to advancing knowledge in the field of sports science and female physiology. We are also grateful to the staff and coaches at the Centre Especialitzat de Tecnificació Esportiva de Rem (Banyoles, Spain) and the Centro Especializado de Alto Rendimiento de Remo y Piragüismo y Residencia de Deportistas (Sevilla, Spain) for their support during the data collection process and for providing access to their facilities. Special thanks to the technical and medical staff for their assistance with participant recruitment and for ensuring the well-being of the athletes throughout the study.